I’m getting an early start on my summer reading list, beginning with a book I’ve read before, The Virgin Suicides. Inside my copy of the novel are treasures of travels past – pressed bougainvillea, scores from a crib game with Ry in Tulum, and scribbled addresses along the Yucatan Peninsula’s shores – similar to the mementos collected by the story’s narrators that allow them to catch a glimpse into the lives of the Lisbon girls (just minus the whole suicide thing and filled with a lot more bliss). If you’re into book reviews, you can find my thoughts on the novel below.

Cecilia Lisbon kills herself twice. Like the fish-flies that fall from the summer sky over the picturesque façade of suburbia, so does Cecilia fall from her bedroom window – “When she jumped, she probably thought she could fly”. This second attempt at death, the one that would take her physical life, is just as disturbing as her first – razor blades to the wrists – and is unsettling to the townspeople of Middle America. An accident, they call it. A way to get out of that house, that decorating scheme, the women of the town gossip. But for one group of boys, Cecilia’s death is only the beginning of getting to know her and the rest of the Lisbon girls, Mary, Bonnie, Therese, and Lux, before all of the girls end their own lives. As the boys piece together their memories of the girls years later, still mesmerized by the artifacts they’d collected during their brief observation of them – Cecilia’s diary, notes on the back of cards of the Virgin Mary – it becomes evident that Jeffrey Eugenides’ story isn’t just about suicide. The Virgin Suicides is a tale about adolescence. Told from a collective viewpoint, it invites readers to share experiences and memories of youth with the novel’s narrators who remember a magical yet fleeting time when they teetered on the fence between the ease of childhood and the realities of adulthood. Adolescence for the boys, like for so many of us, is a dreamlike stage that seems all too good to be true once it’s gone. It is the moment before innocence is, inevitably, lost. It is this time of youth that The Virgin Suicides recalls to create a story about life and everything it encompasses – its stubbornness, its harsh realities, and even its ending, death.

When she jumped, she probably thought she could fly.

The Lisbon girls’ deaths are not morbid, but rather strange yet alluring acts that speak volumes about a town that refuses to see its own decay – the dying elms; the algae scum polluting the air; and the televisions, instead of laughter, talking, and actual physical contact, that have become the way in which people bond and communicate. In many ways, the novel is a reflective piece on the state of society that reveals suburbia as a place filled with irony and sadness – smiling families who are unhappy behind closed doors, unforgettable tragedies that are sensationalized but kept at a distance, and assumptions about the Lisbon girls’ suicides being absurd acts unique to them alone and not a larger social problem that could affect anyone.

Hauntingly beautiful acts of disconnection from the mendacities of the everyday and life lived in middle-class America, the Lisbon girls’ deaths seem to be the act of visionaries who are called from beyond the confines of suburban life to remain as youthful and untouchable by the skies littered with the dying fish-flies and the decay of their town. Death is a way to escape the seemingly eternal sentence of “normal” life that has been so sought after by their parents and community members, religious dogmas and the deceiving allure of the American dream guiding them. The Virgin Suicides does contain suicide, but it is also much more than a story about death; it is a coming-of-age story, a suburban mythology, and an ode to youth and what it’s like to be a teenage girl that holds much beauty. Additionally, The Virgin Suicides is a poetic commentary on the disillusionment of a society caught up in absolute truths of religion, living life the “proper” way, and rejecting individuality. As readers join in on the piecing together of the Lisbon girls’ lives, in which so much more meaning and symbolism is infused, they can’t help but become bewitched by the girls’ story, staring at a distance, never fully understanding or knowing set truths, but still entranced by it all.

The Lisbon girls are old souls, wise beyond their years and aware of the harsh realities of encroaching adulthood. The narrators see this too, noting that “the girls were really women in disguise… [who] understood life, and even death”. Cecilia, although the youngest of the sisters, seems most aware of the confines and manipulation of suburban life, as can be seen in entries she made in her journal, discovered by the narrators, that comment on the cutting down of the elm trees infected with beetles. The boys note that “in cynical entries she suggests that the trees aren’t sick at all, and that the deforestation is a plot ‘to make everything flat’”. One of these entries, written in poetic fragments, is, “The trees like lungs filling with air / My sister, the mean one, pulling my hair”. Cecilia, Lux, Mary, Bonnie, and Therese speak very little in the novel, the notes they leave for the narrators and Cecilia’s journals are some of the only ways in which they communicate with the outside world, but their presence is felt and known by readers through the recollections of the girls provided by the boys.

The trees like lungs filling with air

My sister, the mean one, pulling my hair

In an attempt to make sense of the girls’ suicides, others note a combination of factors, everything from genes for suicidal tendencies, the historical moment in which they are living, and the abuse the girls’ suffered at the hands of strict, religious parents who tried to shield them from the outside world. The narrators of the novel, however, make sense of the girls’ deaths by saying that the Lisbon sisters “became too powerful to live among us, too self-centered, too visionary, too blind”, showing a beautiful dissonance surrounding the girls’ deaths. The girls had to die because they could see too much of the harsh realities of adulthood, of suburban life, of the American dream, and of the way the world was going. Able to see what others couldn’t or, rather, what others refused to see, yet so overcome and blinded by it and the sadness it stirs within them, the girls become weighed down not by life itself but by the heaviness of “mundane facts” evident in everyday suburban life, the torture in “refusal to accept the world as it was handed down to them, so full of flaws”. Their deaths become not a symbol of teenage angst and sadness, but a symbol for a way of seeing, for a need to consider the sickness and decay passing through everyone in a society that has become detached and deteriorated.

In the end, it is not the Lisbon girls’ deaths alone that are important, but rather the narrators’ story of knowing the girls, of loving them, of seeing “their clairvoyance in the wiped-out elms”, and trying to understand their reasons for leaving the physical world. The narrators discover that there are, perhaps, never absolute truths to anything and that their memories of the girls, although insufficient, will continue to live on eternally in their minds. This seemingly simple and short read is layered with complexities. The Virgin Suicides is a mythology for the modern ages set in the normally uninteresting, cookie-cutter setting of American suburbia, commenting on the tragic but beautiful, dreamlike but real, and mundane but fascinating lives of the Lisbon girls.

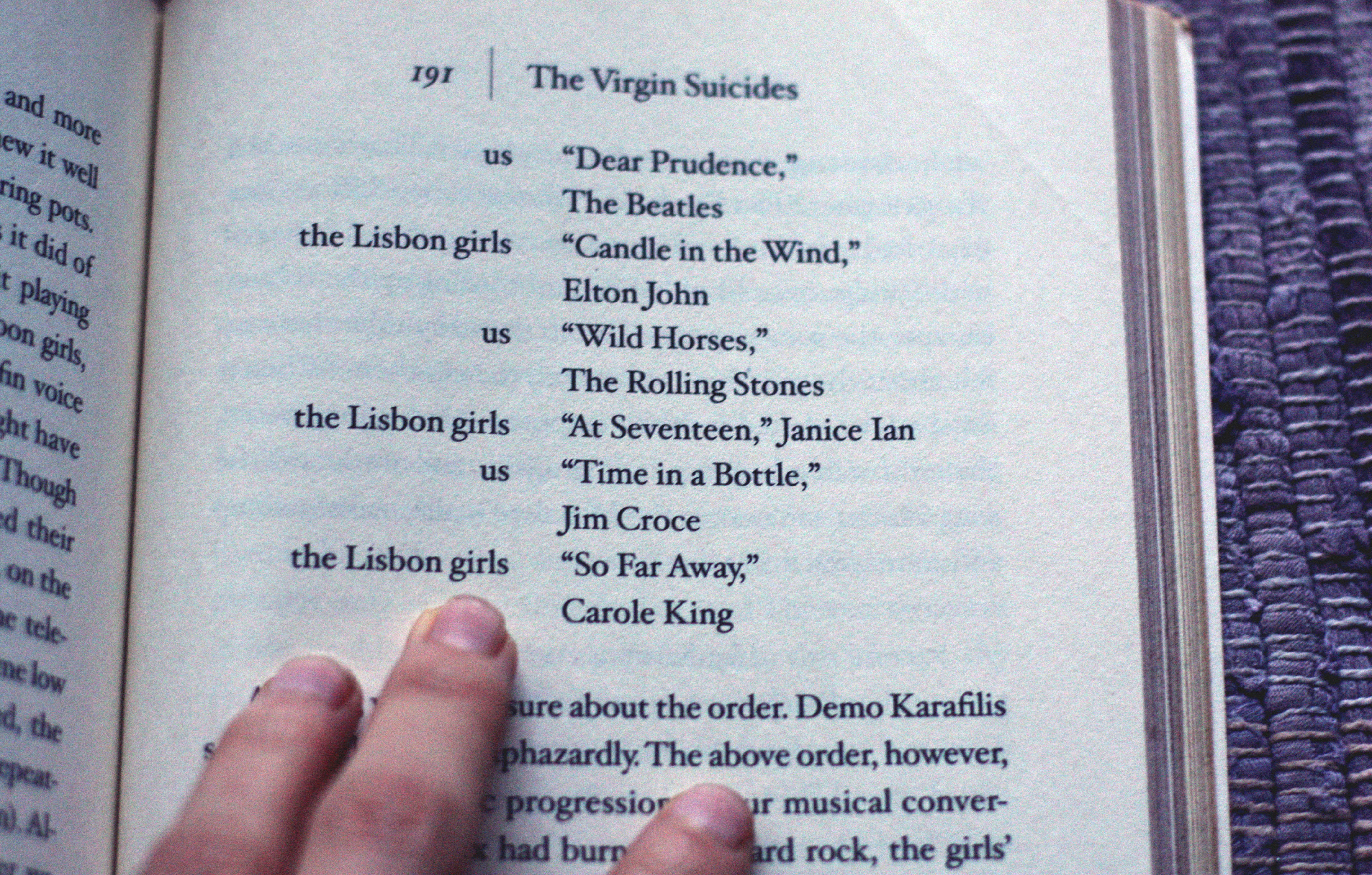

I love Sofia Coppola’s faithful film adaptation of the novel too. Its soundtrack and images have become, for me, so synonymous with Eugenides’ words that I can’t help but hear “Playground Love” and picture Kirsten Dunst as Lux Lisbon when I read the novel.

2 Comments

Laur, this was d e l i c i o u s! Your honey-tongued words make me want to tuck a blanket under my arms, grab my “currently reading” STACK, and truck it out to the garden to enjoy this week of summer-like weather we’re having! [Which is just what I plan to do when I get done with my shift. 😉 ]

I adore re-reading old favorites. They serve to reignite the fires of inspiration for me and immersing myself, once again, in such a familiar story is much like being able to sink back into an almost forgotten dream.

Thank you for sharing, kitten head! ♥

As always, thanks Sarah! ♥

What are you reading right now!? Did you ever get to read Ru? I’m re-re-re-reading Surfacing now for a little syntactic analysis of it. The joy (slight sarcasm). Any good ones I should add to my list?

Thanks for the “push to post” after your dreamy new boards filled with the Lisbon girls and all the greats.

Love, love, love

[p.s. I’d be totally into hearing your sweet word melodies… Sarah Dartez, the BLOG, coming soon? yes? please!]